Posted on 09 Oct 2025

The EU shocked the UK steel industry on Tuesday with an announcement of 50% import tariffs – with no apparent carve-out for metal crossing the Channel.

UK Steel, an industry lobby group, said the plan poses an “existential threat” to British steelmakers. Here’s what you need to know.

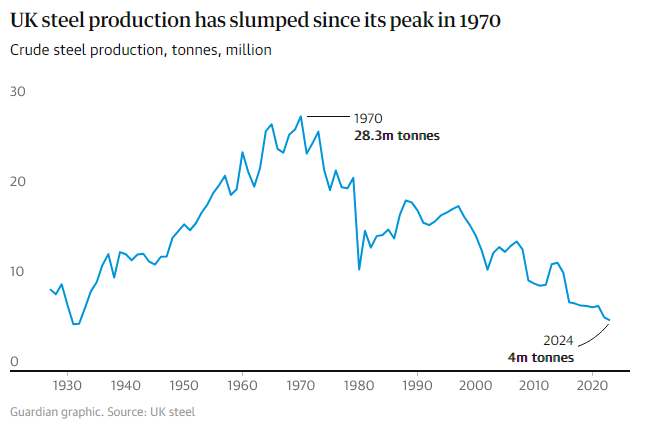

The EU is the UK’s biggest customer: 78% of all UK steel exports, or 1.9m tonnes, went to the bloc in 2024. The prospect of punitive tariffs on a large chunk of that would make many British products uncompetitive overnight.

The reason for that reliance is partly geographical proximity: of the EU countries, Ireland is the biggest buyer. But from 1973 until 2020 the UK was part of the EU, whose forerunner was the European Coal and Steel Community – a single market giving easy access to other members of the trade bloc. Brexit has left the UK out in the cold.

The European Commission has said Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, who are not in the EU but are integrated into the single market via the European Economic Area, will not be affected by the tariffs or quotas.

Its steel industry is struggling. The EU’s steel industry “is as good or as bad as the UK’s”, with plants that have not been modernised for 40 years, one diplomatic trade expert told the Guardian. Steelmakers have been struggling for years with high energy costs – Germany’s are among the highest in Europe (although still smaller than the UK’s).

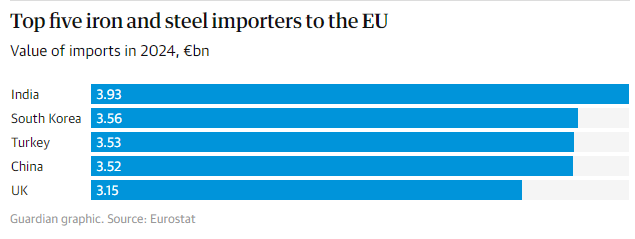

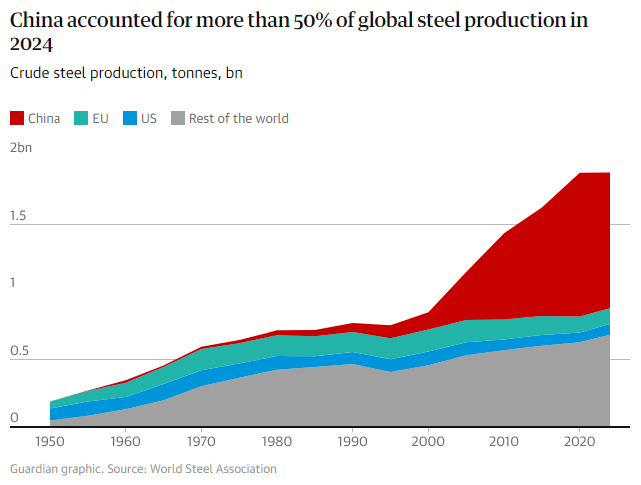

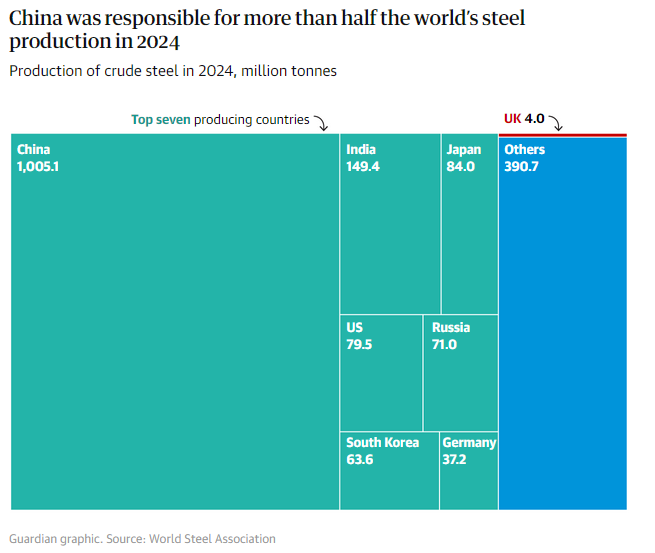

However, the big threat in recent years has been the glut of Chinese steel forcing down global prices, along with the devastating 50% tariff imposed by Donald Trump on US imports of the metal in June.

Current “safeguard” measures to prevent steel dumping are due to expire in June next year, giving the European Commission the perfect opportunity to try to save the sector, which industry commissioner Stéphane Séjourné said on Tuesday was threatened with “collapse”.

A key aim for EU steel industry body Eurofer is to increase the utilisation of its plants, which makes them more profitable. Capacity utilisation has dropped from nearly 80% in 2008 to 65% in 2024; the lobby group wants that figure as high as 85%.

The main measure is an increase in the headline EU steel tariff to 50%, up from 25%.

However, there will still be tariff-free import quotas. That will allow in 18.3m tonnes a year – a steep reduction of 47% compared with 2024 steel quotas.

The key question for Britain and other EU trading partners is how that much smaller quota will be allocated. If the UK were to receive a quota equal to its planned exports (once Tata Steel and British Steel’s exports are back up and running at full tilt after upgrades) then the damage would be limited.

UK steelmakers on Wednesday told industry minister (and former steel executive) Chris McDonald that the UK must push for country-specific carve-outs from the tariffs, and for the UK to quickly replace its own expiring “safeguards” and prevent a flood of diverted steel.

The EU will also add a condition that only steel “melted and poured” in exporters’ markets will count. For instance, that would mean that any steel imported from India to south Wales by Tata Steel would count as Indian, not British, for quota purposes.

Yes and no. The EU has spent all summer railing against Donald Trump’s tariffs as “lose-lose” and “bad for everyone”. But senior officials and Séjourné said they have no choice but to step in to protect an industry that employs 300,000 directly and more than 2 million others indirectly.

Trade commissioner Maroš Šefčovič told reporters on Tuesday that he disagreed with suggestions it was “hypocritical” of the EU to impose tariffs as – unlike the US – the tariffs will comply with World Trade Organization rules and are open to negotiations on quotas, rather than simply being imposed on all and sundry.

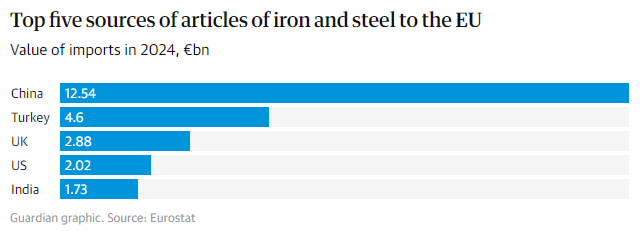

Without doubt, China – and it isn’t even the biggest supplier to the EU after earlier trade measures targeting direct imports. Eurostat data shows India is the biggest direct supplier, exporting almost €4bn to the EU in 2024, followed by South Korea (€3.6bn) and the UK (€3.2bn). EU data shows, in fact, that imports from India went up by just under 90% between 2019 and 2024.

But the rate at which China is producing steel is fuelling global overcapacity. EU officials say the over-supply has “worsened” and become “absolutely untenable”. Not to introduce safeguards would be “extremely damaging” and “possibly fatal”, officials said.

The EU is less concerned about India because it hopes to do a free trade deal by the end of the year. China, however, remains outside any formal trade regime, and the EU feels that, as one of the few open markets left, Beijing is guilty of unfair practices. Pointedly, officials said on Tuesday: “With this proposal, we are again reiterating the invitation to have a serious conversation about that. Regardless of what the Chinese say, we don’t think that this problem of overcapacity is going away.”

The top five steel export destinations for the UK in 2024 were all within the EU. The sixth was the US, where buyers must pay 25% tariffs on imports from Britain – after the two countries abandoned a zero-tariff deal agreed by Trump and Keir Starmer. That gives the UK some advantage over other countries who pay 50%.

Aside from the US, British steel exports would have to contend with the same global glut of Chinese steel seeking a buyer at any price. That is not an attractive prospect.

Another place the UK could look is inwards: Britain imports twice the steel it makes. The chancellor, Rachel Reeves, pledged at Labour’s party conference last week to direct government spending on steel – such as for warships and railways – to British steelworks.

Thyssenkrupp, one of Europe’s biggest steel producers, said in June that it feared the industry was facing “wipe out”, so investors welcomed the protection. Its share price rose by 5.5% on Wednesday, while Sweden’s SSAB rose 4% and ArcelorMittal gained 5% in pre-market trading.

However, carmakers – who use millions of tonnes of steel – were not happy. The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association said it was “most concerned about the inflationary impact”, and that the tariffs go “too far”.

Source:The Guardian